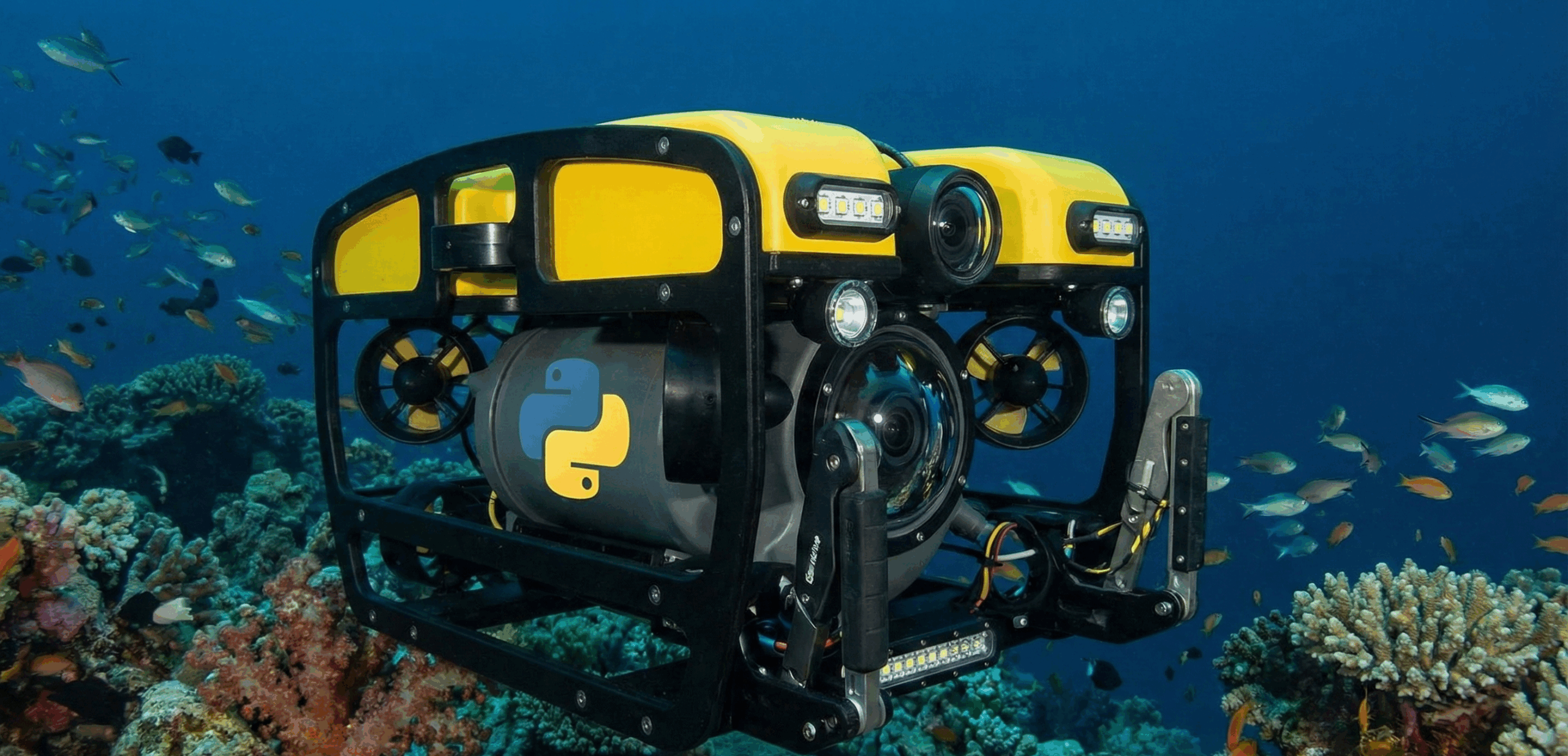

I had always wanted to be an astronaut. Who didn’t right? That was the ultimate adventure, not to mention the fact that one got to wear a cool space suit and work with some very outlandish equipment. When I found out I was blind as a bat however, that little fantasy of mine came to an abrupt end. It would seem however that there was a cheap alternative offering a similar career path of a more ‘aquatic’ nature.

I began to ponder my future and was always fascinated by the underwater world when a commercial diver friend of mine suggested that maybe a career as a working diver might be just what I was looking for. I began to imagine what it might be like working underwater. The only aspect of this world I seemed to associate it with (along with the general public) was that of the underwater welder. This it seemed was the only facet most people understood about this mysterious profession. They, me included, could not have been more wrong.

Off I went to one of the best commercial diving schools on the East coast where I was trained as a commercial deep-sea diver. There I learned many things, knot tying, physics, hyperbaric chamber operation and everything that goes with it. The most fascinating thing however was that of, you guessed it, welding underwater. It was simple enough: Go down in the water, get whatever it is you are going to weld ready, tell topside you are ready and everything goes ‘hot’ and lights up like a Christmas tree. Easier said than done.

The table, the cables and the area where the diver was to practice. I went down the ladder into the shallow water with my little flat square pieces of metal. The exercise went like this; secure the pieces to the welding table and weld the top piece to the bottom piece. They would test the welds by inserting an air hose to a pre-drilled hole that was on the top piece of metal. If you made a good weld, then there would be no air bubble, if your welds were crap (like mine were) bubbles, bubbles everywhere.

I got everything set up, gave everything one more look over and told them to make it hot. I began to weld and felt quite good about my four small beads I had made on the metal square. I finished the job and came up. As I examined my welds I soon realized, as stated earlier, they were not exactly pretty.

When the instructor inserted the air hose, it seemed my beads were somewhat…leaky. I shook it off and told myself I could only get better, I sure couldn’t get any worse. After months of training, I found myself graduating from school and looking forward to all the underwater welding jobs that I would find in my future endeavors. Sometimes the universe has a way of giving you the antithesis of what you are somewhat ready for.

The jobs had come and gone but there had been zero welding jobs, none underwater anyway. My fellow divers had said that those types of activities would be scarce at the power plant jobs we were currently on. I soon got word, however, that I would have an opportunity to work on a very large-scale project that involved something just as interesting as that of welding; underwater burning. I was very curious indeed.

I arrived at a massive lock and dam on the Mississippi River and soon realized this was the biggest job I would probably ever be on. The dive team’s job was to remove old debris and structures left over from a flood that was hindering traffic and the current construction. This involved going down with the torch and cutting things up into manageable pieces that would then be hauled up by a crane. My new situation gave new meaning to the phrase ‘trial by fire’ for I had zilch experience in the burning department.

I suited up and began to try to comprehend everything that I had been told by the other divers who had done this before; how to cut the debris while avoiding lopping off my fingers.

I jumped in the water and slowly made my way to a twisted and mangled pile of steel plates that protruded from a seawall that was slowly being demolished. They lowered a hook from a crane that was loosely attached to this thing so it would not fall on my body when, and if, I managed to cut this thing in half. The torch and rod were lowered down to me and I secured myself as best possible.

I remember I mumbled something to myself that apparently topside interpreted as ‘make it hot’. Knowing that my cutting torch was more ready than me I decided to go for it and struck the metal which resulted in everything lighting up like a murky green glow. As I cut through the steel, my rod burnt fast and hot. I moved the rod across the plate at a decent pace while being sure to keep any digits from being ‘lost’ in the river.

Thirty minutes and a handful of rods later, I felt the piece had been cut all the way through, at least enough of it for the crane to do the rest of the work. It was hauled back to the barge where the crane proceeded to lift my chunk of metal from the shadowy depths. What emerged was anything but pretty. The roughly 3 X 5 foot mass of steel revealed a zig-zag pattern of ugly and inefficient cutting. While the other divers laughed and pointed at the steel, I instead thought about what a great job I had done. After all, I only had about 10 minutes of training topside, and that was just divers telling me to basically not cut my fingers off.

After this, most of the other debris and wreckage I cut underwater was mostly rebar and or smaller bits of steel. I never became a master underwater burner but that experience was one of the most interesting ones I had ever encountered on a dive job…not to mention one of the craziest.

Scott Kilgore is the author of Under Dark Waters: The Life and Distressed Times of a Commercial Diver available at Amazon.com.